by ROBERT C. JONES JR.

UM News

04-19-2019

It was supposed to be a routine operation. Like many times before, a supertanker pulled into Cuba’s Matanzas oil terminal to unload its cargo—crude to meet the island’s rising energy needs. But only this time something went wrong. The tanker sprung a leak, and 27,000 gallons of oil spilled into Matanzas Bay before disaster crews could stop it.

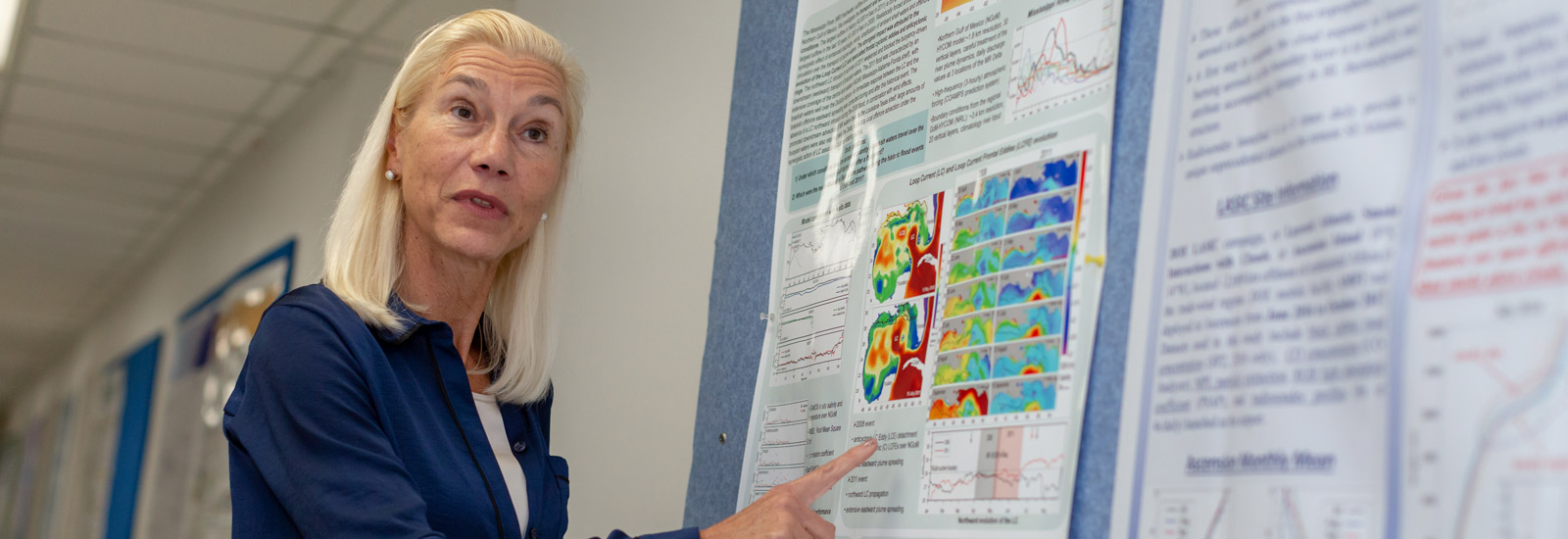

Back at her Virginia Key, Florida, lab, University of Miami coastal dynamics expert Vassiliki “Villy” Kourafalou got wind of the accident and wanted to know if some of the spilled oil would reach U.S. shorelines. So using sophisticated computer models and data from around the Straits of Florida and the entire Gulf of Mexico, she examined the ocean circulation forecasts that her scientific group generates every day. Her conclusion: East-to-west currents along Matanzas would prevent the oil from crossing the Straits.

Florida was off the hook—at least in this case, which occurred in 2018.

But where will the oil go when other spills occur off the coast of Cuba? The answer, said Kourafalou, a research professor of ocean sciences at the Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Science, may lie in the dynamics of anticyclonic eddies that develop near and travel along the island’s northern coast.

Those eddies, which she first described two years ago, naming them Cuban Anticyclones, or CubANs, recirculate water in a clockwise direction, interacting with counter-clockwise eddies in the Straits of Florida between the Keys and Cuba and influencing the Loop and Florida Currents that play a major role in transporting material from one place in the Gulf of Mexico to another—from river brackish waters to fish larvae to nutrients and pollutants such as oil.

“With any spill, the big question is always, ‘Where will the oil end up?’ ” said Kourafalou, whose research on Cuba’s anticyclonic eddies is funded by the Gulf of Mexico Research Initiative (GoMRI) and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

With the U.S. Geological Survey estimating that 4.6 billion barrels of undiscovered oil may be recoverable off Cuba’s northern coast, the island nation has made no secret about its plans for oil exploration and offshore drilling.

But the prospect of offshore drilling in Cuban waters has many environmentalists frightened. They warn that oil from a spill of the magnitude of the Gulf of Mexico’s Deepwater Horizon Macondo blowout in 2010 would reach the U.S. in just a matter of days.

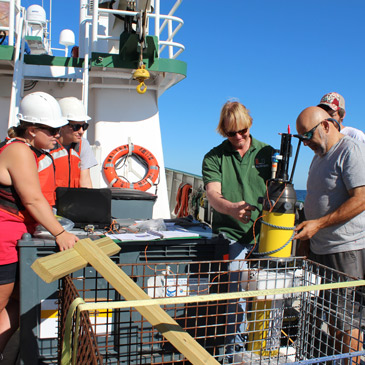

Which is why Kourafalou’s research is being viewed as critically important. Using tools such as satellite imagery, oceanographic data, and the powerful high-computing capabilities of UM’s Center for Computational Science, she and her team are continuously upgrading their predictive models that track the flow of oil from potential spills off the coast of Cuba. They are currently collaborating with the Norwegian Meteorological Institute, which has vast experience in tracking spilled oil.

As ocean circulation patterns in the Gulf of Mexico and the Straits of Florida vary all the time, there are a multitude of different scenarios of where spilled crude would go.

“It’s not just one scenario that says so much of the oil will go the Florida Keys and so much will go to the Bahamas,” said Kourafalou. “It all depends on circulation patterns because the Florida Current is sometimes near Cuba, sometimes near the Florida Keys, and sometimes it has a direct route from Havana to Miami or Palm Beach.”

From an oilrig blowout to a supertanker accident to an oil refinery explosion, Kourafalou’s models deal with the release of oil under different circumstances, either at the ocean's surface or at the sea bottom.

“If it is an offshore spill and the conditions of the Loop Current/Florida Current system are favorable for connecting the spill location and Florida, it would be a dire circumstance,” she warned.

She noted that Cuba has already been hit by environmental disasters—from the Matanzas Bay tanker spill in October 2018 in the north of the island to an oil refinery accident in May 2018, when 12,000 cubic meters of crude and water poured into Cienfuegos Bay on Cuba’s southern coast.

Her study, the Dynamics of Cuban Anticyclones (CubANs) and Interaction with the Loop Current/Florida Current System, is groundbreaking, she said, because up until now, all GoMRI-funded research had focused on the northern Gulf.

“The southern Gulf hasn’t received much attention because data on Cuban waters have not been widely available,” explained Kourafalou. “But we’re preparing the tools to understand the complexities of oil-spill modeling and provide reliable statistics to coastal communities and response managers so they’ll be ready in the event of a disaster in the southern Gulf or anywhere in the Gulf, as the risk for the Florida Keys and the eastern U.S. shorelines is real.”