“If you expose them to a simulated predator stress, the fish that were exposed to oil don’t get stressed compared to those that haven’t been in oil,” McDonald said.

So after a limited exposure to oil, can fish and other marine mammals recover if they swim to cleaner parts of the ocean?

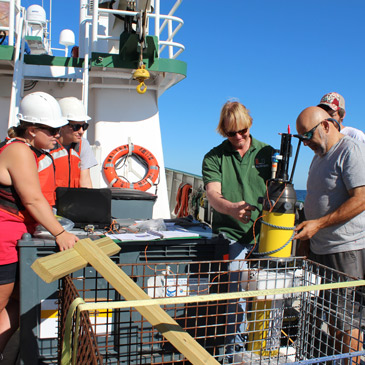

McDonald’s research is also trying to answer this question. Her team exposed the toadfish to a week of oil (mixed into the water at low concentrations), two weeks of oil, and to 28 days of oil, and then put them back in clean water for varying time periods. They are now investigating whether the fish are able to recuperate.

“After seven days of exposure, followed by seven days of being back in clean water, they still cannot mount a stress response, so they are not recovering,” McDonald said, adding that they are still waiting to test the fish exposed to oil for longer time periods.

Since toadfish are extremely resilient and can even survive without water for close to 24 hours, McDonald said that exposure to oil could be even more damaging to other, more sensitive fish. In the future, McDonald’s team will likely test other fish species, such as mahi-mahi, to see how they respond, she added.

“Reliance on cortisol differs between fish species, but the receptors, enzymes, and hormones involved in response are constant across animals that use cortisol as their stress hormone,” she said. “So if a particular receptor involved in the stress response of a toadfish is sensitive to oil, we are likely going to see the same problem in bottlenose dolphin, too.”

McDonald’s research is set to wrap up at the end of this year, yet there are still a few remaining questions that her team will try to answer in the coming months. First of all, will toadfish exposed to oil ever be able to recover fully from this trauma? And more importantly, why are fish that have been exposed to oil left with the inability to physically react to stressful experiences?

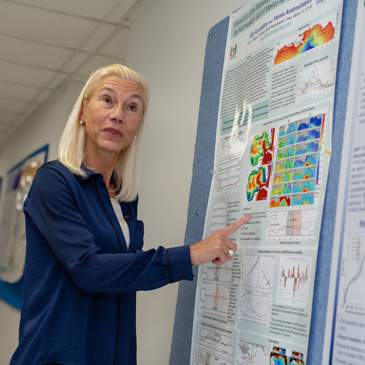

“We’re trying to analyze the mechanism of why these fish are not mounting a stress response,” McDonald added, stating that she and her researchers are looking at gene expression, enzyme activity and even cholesterol levels, to isolate the issue. “The goal of our research is to determine where the problem is, which we are still working on.”