by ROBERT C. JONES JR.

UM News

04-19-2019

In the end, it probably did more harm than good.

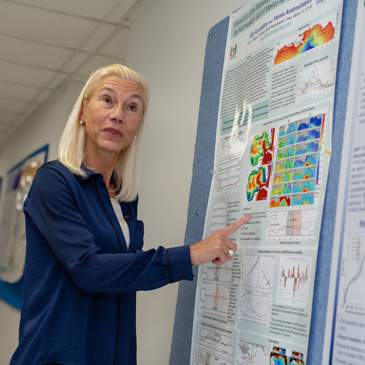

That’s one of the conclusions of a study led by University of Miami researcher Claire Paris-Limouzy that found the chemical dispersant used to break up the oil after the Deepwater Horizon spill in the Gulf of Mexico in 2010 was ineffective and unnecessary.

In an unprecedented response to the Deepwater Horizon spill, British oil giant BP injected massive amounts of a dispersant called Corexit at depth in an attempt to push back the spread of the oil. But the dispersant didn’t work due to the extreme depth of the crude and may have actually contributed to the ecological damage by suppressing the growth of natural oil-degrading bacteria and increasing the toxicity of the oil itself, according to Paris-Limouzy, a professor of ocean sciences at UM’s Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Science.

The study, which focuses on subsea dispersant injection, is groundbreaking in that Paris-Limouzy and her team used data publicly available through the Gulf of Mexico Research Initiative Information and Data Cooperative.

The study, which focuses on subsea dispersant injection, is groundbreaking in that Paris-Limouzy and her team used data publicly available through the Gulf of Mexico Research Initiative Information and Data Cooperative.

“Our earlier work using computer modeling and high-pressure experimental approaches suggested that pumping chemical dispersants at the spewing wellhead may have had little effect on the amount of oil that ultimately surfaced. But empirical evidence was lacking until the release of the BP Gulf Science Data. When completely different approaches converge to the same conclusion, it is time to listen,” said Paris-Limouzy. “There is no real trade-off because there is no upside in using ineffective measures that can worsen environmental disasters.”

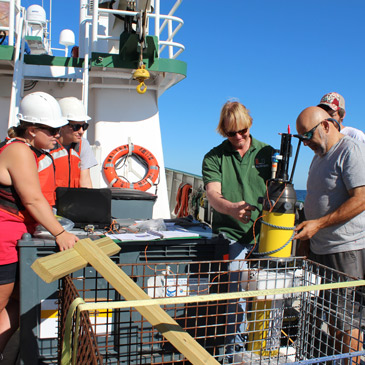

As the oil industry drills in deeper and deeper water, it must find alternative strategies to manage blowouts, she said. The “capping stack” method, used by BP to stop the wellhead outflow, may be a more effective first response strategy. Biosurfactants, which are less toxic and more efficacious to biodegeneration, may offer a viable alternative for oil spills in shallow waters.

“We need to focus on prevention rather than response,” said Paris-Limouzy, warning that dispersants actually linger in the water column, harming even the smallest of marine organisms.

“That’s one of my biggest concerns—that we’re not paying enough attention to the water column,” she said. “All life started with plankton. Everything started as tiny organisms. If we’re affecting the plankton, we’re really killing the food chain.”

The study, which focuses on subsea dispersant injection, is groundbreaking in that Paris-Limouzy and her team used data publicly available through the Gulf of Mexico Research Initiative Information and Data Cooperative.

The study, which focuses on subsea dispersant injection, is groundbreaking in that Paris-Limouzy and her team used data publicly available through the Gulf of Mexico Research Initiative Information and Data Cooperative.