by Robert C. Jones Jr.

UM News

07-12-2019

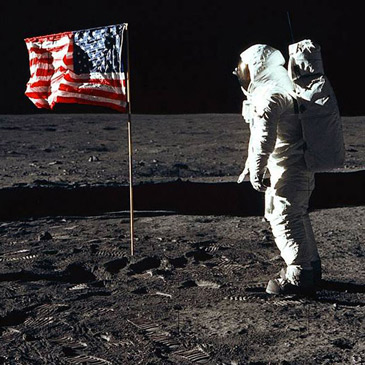

It wasn’t a Buck Rogers comic book story Luis Rodriguez’s third-grade teacher was lecturing about, but the real thing.

Astronauts, she told his class, had actually blasted off from Earth aboard a rocket ship, traveled a quarter of a million miles into space, and safely landed and walked on the surface of another world.

Though Rodriguez was only 8 at the time of that history lesson, the magnitude of what astronauts Neil Armstrong, Buzz Aldrin and Michael Collins accomplished didn’t escape him. “It made me believe we could do anything,” he recalled.

Now, 50 years after the successful Apollo 11 mission, NASA has set its sights on going back to the moon. And Rodriguez, born nearly two decades after Armstrong’s historic “giant leap for mankind,” is part of the latest generation of NASA engineers who are creating new technologies to safely return humans to our planet’s only natural satellite—and perhaps hurl them to other worlds.

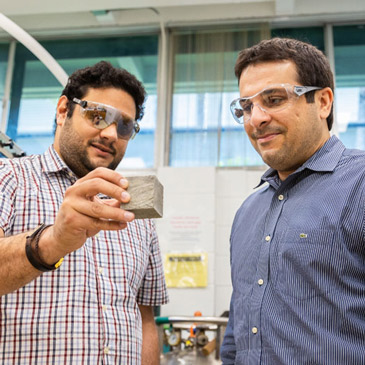

Since completing his postdoctoral research at the University of Miami’s College of Engineering last February, Rodriguez has worked as an electrical power systems analyst at NASA’s Glenn Research Center in Cleveland, Ohio, where he and other engineers are conducting experiments on small, lightweight Stirling engines that won’t wear out over the lifetime of a space mission.

“It’s an awesome place to work,” Rodriguez said of his time at Glenn, going on to explain the intricacies of Stirling engines and the great promise they hold for space exploration.

How do they work? A radioisotope element provides heat energy, and the Stirling engine converts it to electricity. Free-floating pistons inside the engine move continuously at high frequency. But the pistons never make contact with other engine parts, eliminating wear and tear.

NASA engineers at Glenn recently operated a free-piston Stirling engine at full power for over 110,000 hours of cumulative operation—the equivalent of 12 years. And the engine is still running without issue. Which is important because NASA wants to go deeper into the dark frontiers of our solar system, where humans have never ventured.

So Rodriguez and other engineers at Glenn are going a step further, working on Stirling engines for a new type of radioisotope power system called Dynamic RPS, which would use less fuel on journeys that require more efficient and powerful spacecraft and would sustain power for deep-space operations such as conducting science experiments and transmitting data back to Earth.

“I’ve used what I’ve learned from every engineering course at UM to help me in this job so far,” said Rodriguez.

Born in Colombia, he wants to eventually become an astronaut. It’s been a lifelong goal of his ever since that third-grade history lesson on the Apollo 11 mission. “It’s the challenge of going beyond your bounds that drives me, of exploring and going on an adventure—like Neil Armstrong stepping on the surface of the moon,” said Rodriguez, a U.S. Air Force veteran.

Going back to the moon and beyond, he said, is imperative.

“We’ve always been explorers,” explained Rodriguez. “The technologies that would be spawned from such missions would benefit all of society.”