College of Engineering alumnus Frank DeMattia was just 21 years old when he went to work at NASA on the powerful Saturn V rocket.

by Robert C. Jones Jr.

UM News

07-18-2019

CORAL GABLES, Fla. (July 18, 2019) – The rows and rows of strip chart recorders seemed to go on forever, their long rolls of paper being expelled as more and more data was compiled.

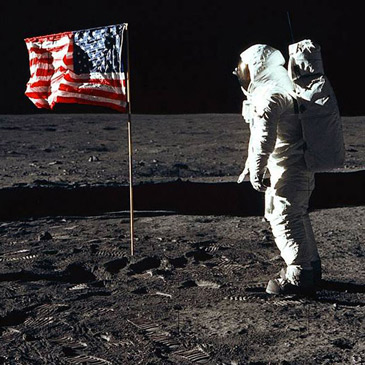

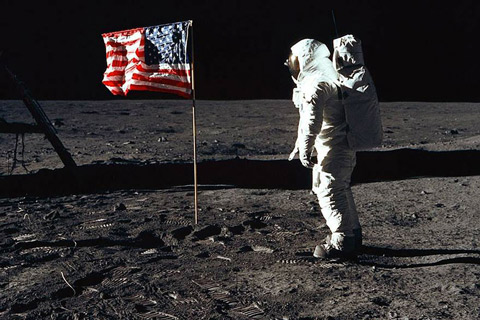

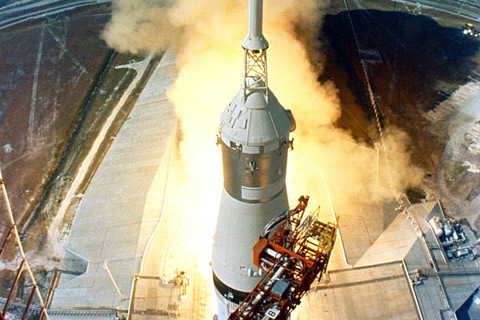

It was just past 8 a.m. on July 16, 1969, and instrumentation engineer Frank DeMattia was sitting at a console in the back of the Launch Control Center at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida, monitoring a readout of the pressure and temperature inside the Saturn V rocket’s second stage fuel tanks.

If the readings were too high, the 21-year-old DeMattia, just five months removed from graduating with an engineering degree from the University of Miami, would have to scrub the launch.

“It was one of the mission critical systems of the rocket,” he recalled, “and it was my responsibility to call an abort if those red lines went beyond limits.”

They didn’t. The pressure and temperature of the liquid hydrogen and liquid oxygen fuel mixture remained stable, and at 8:32 a.m. EST, the powerful Saturn V, with all other systems go, blasted off from Launch Pad 39A, sending astronauts Neil Armstrong, Buzz Aldrin, and Michael Collins on the greatest adventure in human history.

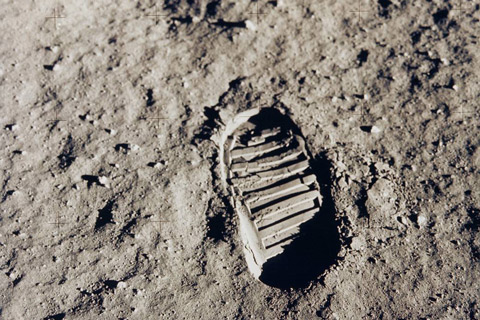

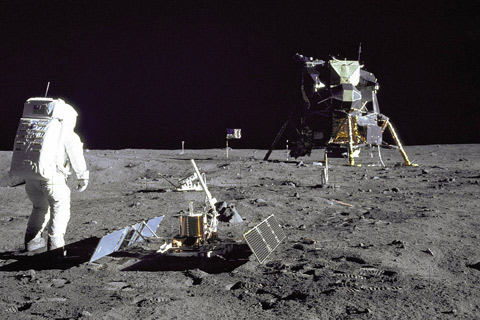

Today, 50 years after the Apollo 11 mission that landed the first humans on the moon, DeMattia is a consultant to the aerospace and defense industries, the many key engineering positions he held with North American Rockwell and Boeing now behind him. But one thing hasn’t changed—the modesty he exudes when describing the role he played in ensuring that Armstrong was able to take his “giant leap for mankind.”

“Twenty thousand companies and 400,000 people worked on Apollo 11. I was just a very small part of it, a cog in a very huge machine,” he said.

Still, his résumé while working on the Apollo program speaks volumes.

At UM, DeMattia was a whiz at digital electronics, the same technology built into the instrumentation system used to monitor the Saturn V rocket’s second-stage fuel tanks. “I’m sure,” he surmised, “that the folks at North American Rockwell said, ‘We’ve got this kid right out of college who knows this stuff. Let’s put him on that.’”