by ROBERT C. JONES JR.

UM News

09-26-2018

CORAL GABLES, Fla. (September 26, 2018) – A PVC pipe fashioned into a pole and a few demijohns packed neatly away in the back of his van, Larry Brand sets out from his South Miami home just before dawn and races north along U.S. Route 27, headed for one of the hotspots of this year’s massive toxic algae bloom outbreak.

In a little over two and a half hours, he arrives at his destination—the Caloosahatchee River, just outside the city of Fort Myers—and with one of the sample bottles fastened to his makeshift pole, draws a one-liter sample of water from the tributary.

Brand would repeat this process at a handful of other bodies of water that day, capping the bottles and loading them back into his van for the drive back to Miami. It would be dark by the time he got home. “It’s usually a full day’s work, depending on where I go,” said the phytoplankton ecologist at the University of Miami’s Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Science.

From Lake Okeechobee to the St. Lucie Canal to the southern Everglades to Florida Bay, Brand collects samples from Florida waterways on a regular basis, taking them back to his Rosenstiel School lab to culture and measure levels of harmful algae.

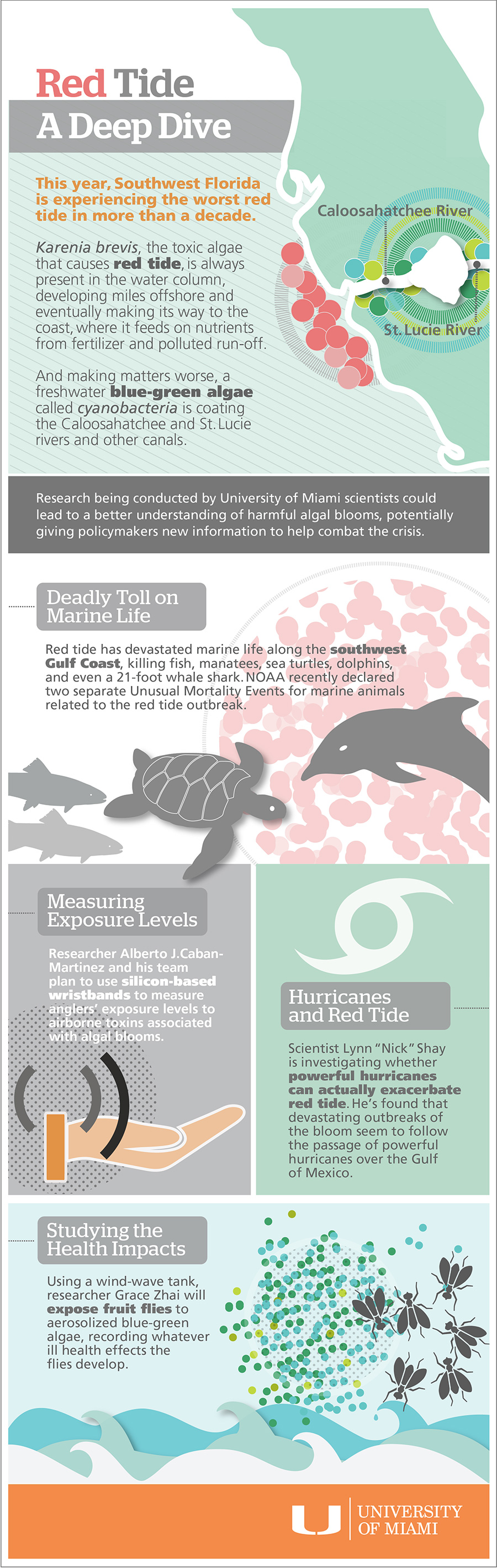

One-Two Punch

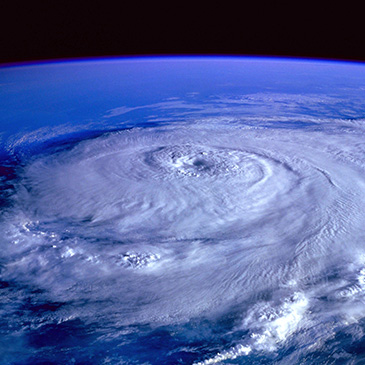

This year, his work is doubly important. Not only is the toxic algae Karenia brevisstill causing the worst red tide along Florida’s southwest coast in more than a decade, darkening Gulf of Mexico waters, killing marine life and triggering respiratory distress and other ailments in locals and tourists, but also a freshwater blue-green algae called cyanobacteria has coated the Caloosahatchee and St. Lucie rivers and other freshwater canals.

What that means for the long-term health of residents remains unclear. But Brand, a professor of marine biology and ecology, is part of a UM team of scientists trying to find out.

“In one sense, algae are the good guys. If you didn’t have any algae at all in the ocean, you wouldn’t have any other life because it’s the basis of the food chain. But sometimes the algae get out of control. We know that red tide toxins get into the air and into seafood. The effects are immediate, and that’s what most of the research has concentrated on,” said Brand, noting that Karenia breviscan cause gastrointestinal and neurological disorders that develop within minutes, hours or days after exposure. “But now, we’re looking at these toxins in blue-green algae that can have long-term effects. And the big question is, could they be getting into the air?”

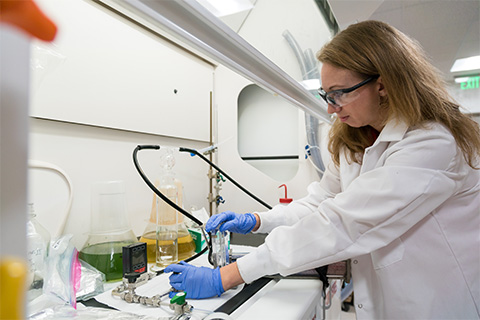

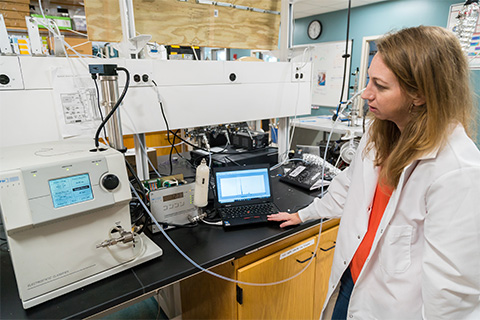

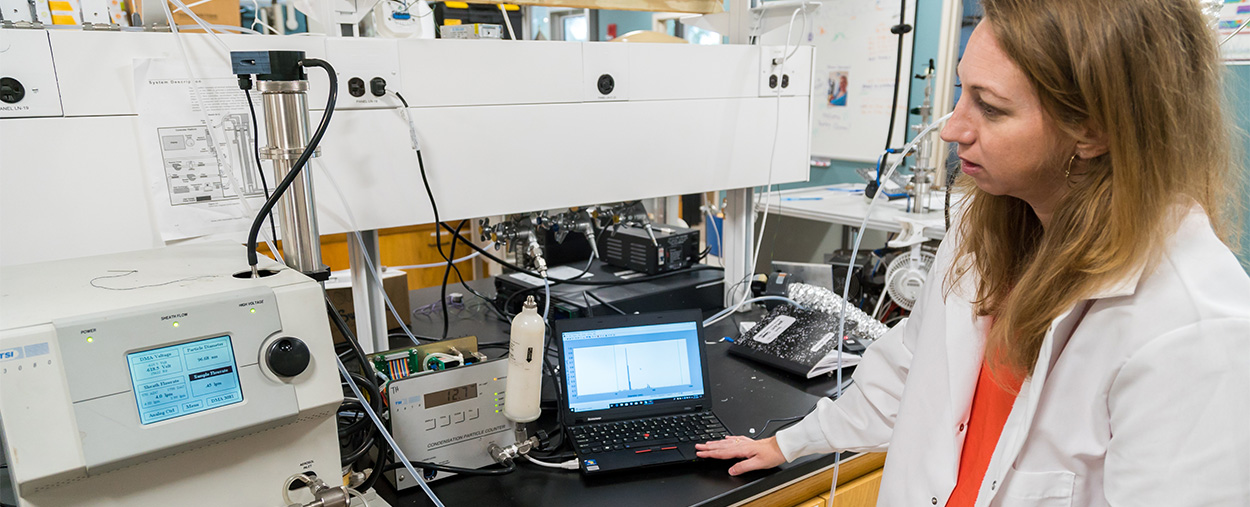

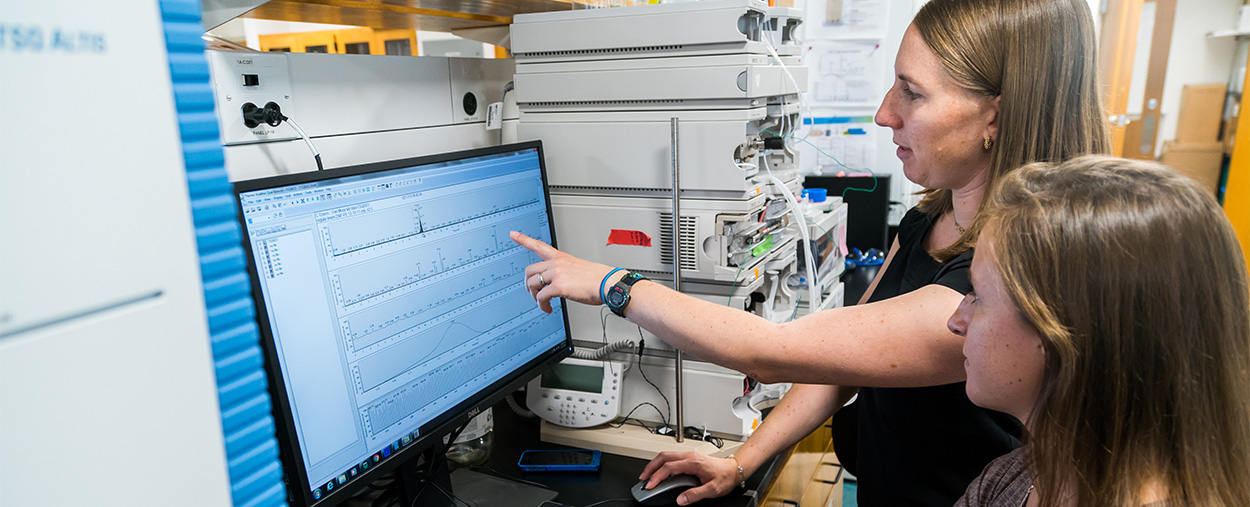

That’s where Cassandra Gaston and Kimberly Popendorf step in. With assistance from their students, Michael Sheridan and Kaycie Lanpher, the two Rosenstiel School researchers have been testing air samples collected near the same rivers, lakes, and streams where Brand has been gathering water samples. “We’re trying to find out whether or not some of the different harmful algal blooms that we get in Florida other than red tide can become aerosolized, specifically cyanobacteria, which there’s not a lot of data on,” said Gaston, an assistant professor of atmospheric sciences.

So the two researchers subject the air samples to a chemical extraction process, testing for the presence of any toxins. And in another experiment, they plan to place blue-green algae water samples provided by Brand into the smaller of two wind-wave tanks at the Alfred C. Glassell Jr., SUSTAIN laboratory, subject the samples to different wind speeds, and measure the concentration of toxins in any water-to-air transfer that occurs.

“We’d like to put all of our data together to come up with some means of having a degree of predictability,” said Popendorf, an assistant professor of ocean sciences.

It will be the first such usage of the tank, according to Brian Haus, professor of ocean sciences and director of the SUSTAIN lab.