“Heavy metals, toxins and pesticides in our oceans—we don’t know exactly how they affect sharks, but it probably has some sort of adverse effect,” said Moorhead. “It’s not good for humans, so who knows what it does to sharks.”

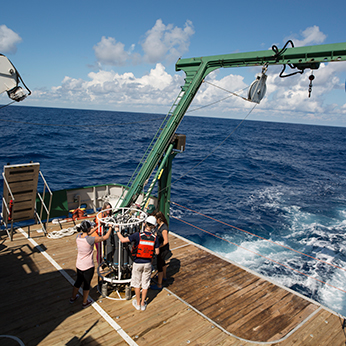

Moorhead is trying to find out. On shark-tagging expeditions, she collects blood samples from nurse sharks, spinning the vials in a centrifuge onboard the boat to isolate the plasma from other blood components. She analyzes the blood samples back at the SRC lab, paying particular attention to the energy metabolites that give her a clue as to how healthy the shark is.

“A shark with an abundance of energy has enough to reproduce, hunt and migrate,” she explained. “It doesn’t have to sacrifice one thing or the other for lack of energy. If I can show that even nurse sharks—one of the more tolerant species of sharks—are being affected by urbanization in some way, those results could be shared with policymakers to raise awareness about sharks and help protect their habitats.”

Moorhead is part of what Neil Hammerschlag, research associate professor at the Rosenstiel School and SRC’s founding director, calls the new generation of marine scientists—women who are the next Rachel Carsons, Sylvia Earles, and Ruth Turners.

“That’s one of the things I like most about our team,” said Moorhead. “It’s 60 percent female.”

“Our strong group of female students are role models to the middle and high school girls we take out on shark-tagging trips as part of our outreach activities,” said Hammerschlag, who co-founded F.I.N.S. (Females in the Natural Sciences). “They inspire them to pursue careers in STEM and demonstrate that science and field work are not only for males.”

Patricia Albano became smitten with sharks about four years ago, when she volunteered as a counselor at a marine camp for high school students during her freshman year at UM. “We took the kids on shark-tagging trips,” said Albano, who earned a bachelor’s degree in marine science and biology. “I knew then that I wanted to study sharks and make an impact on raising awareness about them.”

So in her last two UM undergraduate years, Albano participated in SRC activities, and she did her senior thesis research project on the effects of capture-and-release on nurse and blacktip sharks.

She is entering her first year as a master’s student in marine ecosystems and society, and will travel to Cape Town, South Africa, to study the movement of sharks in a marine reserve located near that city. “There’s a longline fishery on the outskirts of the marine reserve. Sharks are protected inside the reserve, but when they swim outside of it, they’re vulnerable to being caught,” Albano explained. She will use acoustic tags to track the sharks’ movements, with the goal of determining how to better protect the creatures when they venture outside the confines of the reserve.

Her favorite shark? The hammerhead. “They have special abilities other sharks don’t,” said Albano, referring to its oddly shaped head, which is called a cephalofoil and may actually help them swim faster, see better, trap fleeing prey on the sandy seafloor, and perhaps enhance their ability to detect electrical signals and smells.

After graduating from Seton Hall University with an undergraduate degree in environmental studies, Andriana Fragola enrolled in the Rosenstiel School’s Master of Professional Science program, where she is now active in SRC, participating in shark-tagging expeditions and studying a type of parasitic lesion that is sometimes found on the epithelial skin layer of blacktip and bull sharks.

“There’s evidence that shows that the area on the shark’s skin where the lesion is located could be compromised—less efficient and effective in preventing bacteria from invading,” said Fragola, explaining that her study is one of the first of its kind because it examines sharks in their natural habitat while other bacterial investigations typically focus on sharks in captivity.

Her study has far-reaching implications on the understanding of the immune system of sharks. “We know they have strong and robust immune systems, but we need to learn more about their resistance to different things,” she said.

Research being conducted by Elana Rusnak could help in that regard. The first-year graduate student at the Rosenstiel School is studying the immune system of sharks, drawing blood samples from nurse sharks in the field.

“We know what a healthy human looks like immunologically. We know what an unhealthy human looks like immunologically,” explained Rusnak, 23. “The problem is we don’t know a lot about shark health. We can get body condition. We can get blood parameters. But that doesn’t really tell us if they’re healthy or not.”

Her goal is to establish a baseline for shark health, which requires that she isolate certain protein biomarkers in sharks’ blood to get a measurable indicator of normal biological processes. But isolating the protein is proving difficult. “In a clinical setting or in labs that have captive sharks, their condition can be studied over time and tests can be run, but we have only one shot to learn as much about these animals in only a five-minute workup in the field.”

Rusnak will more than likely have completed her graduate degree long before she is able to establish that baseline, leaving work for others to build on but also to complete when she starts her doctoral studies.

Said Rusnak, “I’ve never been more passionate about something.”