Over the next weeks, the students will spend their class time refining and combining the dozens of individual drawings they made of the synagogue’s lofty interior spaces and of many of its intricate details and monumental mahogany furniture—the ark on the bimah that holds 18 precious torahs, the reading platform where the spiritual leader conducts services, the towering brass candle chandeliers that are lit only on Yom Kipper and for weddings, the majestic columns that soar skyward, the three Dutch gables and semi-circular vaulted ceilings, the impressive organ added in the 19th century, and the latticework of timbers that ancient shipbuilders so expertly fashioned to form the attics.

“There is a wisdom embedded in these structures that goes back generations,” Hernández said, trying to keep the skullcap men are required to wear inside the Snoa, as the house of worship is widely known, atop his mane of silver hair. “Every culture embeds that wisdom in its built environment, and we can’t lose them for that reason. They are like textbooks. We can learn from them, and adapt them for contemporary use.”

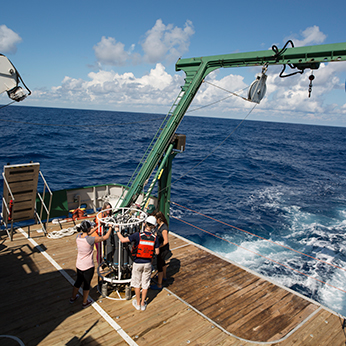

As he spoke, the drone operated by the Center for Computational Science’s Chris Mader, director of software engineering, and Amin Sarafraz, a computer vision expert, buzzed up and down the Snoa’s north wall. Over the week, it would take thousands of photos that, stripped of all perspective and merged into single images, would provide students the bird’s-eye views that architects have used to convey their plans since antiquity.

“The concept is as old as Egypt,” said Hernández, who directs the School of Architecture’s Historic Preservation Certificate Program. “It hasn’t changed. It’s the pencil that keeps changing. The drone is like another pencil. It just so happens it’s a very fast pencil.”

Intrigued by that changing pencil, Mathews, the art historian, is exploring how old and new technologies can be used together to create a more comprehensive understanding of historic structures.

It was UM’s multidisciplinary work in Cuba—and the School of Architecture’s pioneering collaborations with the Center for Computational Science to map informal cities—that gave UM’s first lady the idea for developing an architectural and historical survey of the Caribbean’s Jewish heritage. As the daughter of a Holocaust survivor and the director of the Institute for Advanced Study of the Americas, Knaul is keenly aware of the need to preserve the history of Jews who scattered around the world, especially in Latin America and the Caribbean.

She and UM President Julio Frenk have explored synagogues around the world and on their 20th wedding anniversary in 2015 visited Curaçao, where they were warmly welcomed by the Mikvé Israel-Emanuel Synagogue congregation, which included UM alumni and parents of students. There the idea for the pilot project was sown, and later reinforced on a visit to the reconstructed synagogue in Barbados—potentially next on the project list.

“What is so unusual about UM is we have all the pieces, all the experts, to do this,” Knaul said. “What the School of Architecture did with Cuban churches is transferable knowledge, so we are in an ideal position to develop and maintain architectural information on Jewish synagogues in the Caribbean, working with their own home communities.”

Lovingly cared for, the Mikvé Israel-Emanuel Synagogue is already a well-preserved Sephardi synagogue, one that has retained the liturgy, rituals and customs of the Jews who originated from Spain and Portugal and arrived on the island in 1651. But today it attracts far more tourists and school children on daily visits than worshippers at weekly services. Only about 300 Jews remain in Curaçao, and half belong to the Ashkenazi synagogue, where Jews of central or Eastern Europe descent feel more at home.

“When this synagogue opened in 1732, there were 2,000 Sephardic Jews on the island—half the population of Curaçao and more Jews than in all of North America,” said Avery Tracht, the synagogue’s hazzan, or cantor, who serves as its spiritual leader. “Now they can’t afford both a rabbi and a cantor so I fulfill both roles.”

For the second part of their semester, the preservation studio students will propose additions to the auxiliary spaces in the Snoa’s courtyard that perhaps would draw more people to the historic treasure while honoring its rich history.

As he climbed through the attics and crawled to the rooftop, Valdivia couldn’t help but reflect on that history, and on the ancient designers whose original drawings for the Snoa were lost long ago.

“Even in the heat, I lost track of time,” he recalled. “The air was different and I’m not only talking about the dust. You can feel the energy of the place up there. You can see the intentions of the design. You’re walking through the skeleton of the building, seeing it from the inside out.”